[A heads-up before we begin. What you’ll find below is not an academic, peer-reviewed article, but neither is it a simple post. It’s a bit of both, I guess. If that sounds confusing, it’s because it is: I started revising this piece thoroughly, but it took me a lot of time to figure out what I wanted it to be. When I finally got the gist of it, thanks to some helpful feedback, I got swamped again with approaching deadlines and other academic commitments. As the piece is too substantial to be left in the (digital) drawer, but still too rough to be published elsewhere, I opted to leave it on my reliable good ol’ personal blog. The current version includes my critical thoughts on the issues at hand (the crisis affecting the US mainstream comic book industry and the corporate and editorial management of Marvel’s iconic character Spider-Man), along with academic works, blog posts, long-form YouTube video essays, and some key historical references that I believe are important for understanding the broader context. I may want to develop this post into one or two more refined and presentable pieces in the near future, but for the time being this is the version I’ll stick to, if only because I don’t have much time to devote to yet another project, however fascinating it may be. I hope you’ll find something of interest in the following musings, ramblings, and mumblings! Cheers.]

“If [Peter Parker]’s still fouling up as an adult, he just isn’t a hero anymore. He’s pathetic.”

Marv Wolfman in DeFalco (2004: 78)

Prologue

The US mainstream comic book industry is facing an ongoing crisis marked by dwindling readership; meanwhile, Japanese mangas, graphic novels, and comic books targeted at a younger demographic enjoy an unprecedented success (Medina 2019; Barnett 2019; Kemner and Trinos 2024; Banks 2026). This turbulent shift in reading preferences comes on top of a disturbing sequence of sexual misconduct and/or assault accusations against celebrated mainstream authors (to name just a few, Warren Ellis, Jason Latour, and, lately, Neil Gaiman; McMillan, Drury and Couch 2020; Shapiro 2025), the dire aftermath of the systemic disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic (Thielman 2020), the financial exploitation and cannibalisation of artists and writers by the corporate Hollywood system (Thielman 2021), the double whammy of machine learning and AI art generated through intellectual theft and copyright infringement (Nam 2024), the baffling disappearance of publically available, industry-wide comparative sales chart (MacDonald 2023; MacDonald 2025a), new tariffs on paper import affecting print costs that exacerbate ever-increasing prices (Myrick 2024; Gagliano 2025), and the bankruptcy of comic book distributor Diamond (MacDonald 2025b; for a timeline of the still developing situation see Johnston 2025a). If one were inclined to believe in such things, it could be argued that the satirical curse – or accursed satire – novelist, comic book writer, and ceremonial magician Alan Moore placed on the comic book industry as a whole via his novel-size novella “What We Can Know About Thunderman”, conceived as an act of symbolic retribution for its “predatory and immature” practices, has finally begun to work its magic (cit. from Robertson 2024; see Ambasciano 2023 on Moore 2023) [1].

(Un)creative fodder

It is neither unfair nor especially controversial to suggest that, aside from a handful of recent and qualitatively remarkable exceptions, many of the Big Two’s historic flagship titles has long been locked into a repetitive loop: plots are devised to endlessly recombine archetypal narrative elements in fractal-like permutations drawn from the same exhausted diegetic matrix, generating storytelling tropes that have grown increasingly stale and uncreative. Given that the publishing divisions of Marvel and DC are infinitesimal cogs in the corporate entertainment machines of Disney and Warner Bros. respectively, this is rather unsurprising. In the words of journalist Catherine Shoard, “Hollywood, it appears, is stuck on repeat, sucked with an ever-more deafening gurgle into a death cycle of creative bankruptcy desperately presented as comfort food” (Shoard 2025). Through the ongoing barrage of uninspired relaunches and reboots we can clearly observe the industry version of Tancredi Falconeri’s nihilistic and opportunistic motto “if we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”, immortalised, only slightly rephrased, by French thespian Alain Delon in the movie version of Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel The Leopard (1958), and recently retold by Italian actor Saul Nanni in Netflix’s “steamy, sumptuous” adaptation (Aroesti 2025).

Briefly put, new titles struggle to gain traction and are continually cancelled, while ongoing ‘legacy’ titles are forced to periodically revert to the status quo ante, erasing any real progress in the characters’ story arcs (when present). The prioritisation of artificial and short-term sales boosts, achieved through the relaunch of these series with a shiny new “issue #1” stamped on the cover or company-wide crossover events involving several titles at once, rarely comes with sufficiently coherent in-universe justifications. Consequently, the brief sales spikes resulting from these editorially mandated resets fade quite rapidly, which in turn prompt publishers to relaunch the same titles in the span of a few years or even mere months. Other profitable marketing strategies sidestep the content entirely while focussing on the product itself, but they do so at the expense of collectors and die-hard completionists, risking disaffection and disengagement (cf. the proliferation of variant covers, incentive covers, and ‘blind bags’; Avila 2019; Johnston 2025b). Perhaps the monthly floppy has had its day (at least for the time being), in which case bold and unprecedented editorial decisions would be required to halt the industry’s hemorraging, especially considering that every new monthly issue must fight not just for attention in an overcrowded marketplace, both on shelves and on screens, but also compete with celebrated, and often better executed, past runs of the same characters canonised in best-selling and readily available, self-contained (physical or digital) volumes. It may also be that the superhero genre itself (as it has been conceived in the United States after the Bronze Age) is undergoing a cyclical downturn. Whatever the reason, the US mainstream production’s reliance on the fossilised template of a single genre has made it particularly vulnerable to broader societal or generational changes when compared to Europe or Japan (cf. the recent Jim Lee interview in Maeda 2026). Finally, inadequate salaries for artists and writers and minimal acknowledgment of creators’ rights and contributions exacerbate the problem, as such factors understandably limit the appeal of taking on a job in the industry and shrink the available pool of potentially interested creators, and so the qualitatively self-defeating loop can start again – at least until corporations go bankrupt or their intellectual properties finally enter public domain (for a different opinion cf. Brevoort 2024).

On the other hand, a significant portion of good contemporary storylines involving ‘legacy’ characters can rarely grow to express the full potentialities that are unique to sequential storytelling, even within the constraints of the mainstream, because they exist mostly as first drafts, rough outlines, or ashcans for the media conglomerates that own the Big Two [2]. In the surprisingly sincere words of Senior Vice President of Publishing and current X-Men Group Editor Tom Brevoort,

“[…] the purpose of Marvel Publishing is to be out in front, the tip of the spear, generating new ideas and new stories that can serve as creative fodder for eventual film and animation development. So trying to revert things to 1992 or whenever would seem to be defeating the purpose in a major way. Better, I think, to try to develop new status quos that future X-Men projects in film and television can draw from” (Brevoort 2025a; my emphasis).

The multiple crises currently affecting a shrinking Hollywood industry casts Brevoort’s ancillary view of mainstream comic book production as overtly optimistic if not somewhat self-sabotaging (Keegan et al. 2023; Morris 2024; Miracle and Canes 2025; Gumbel 2025; cf. Ambasciano 2024; for a contrastive view on the issue see Lee’s emphasis on comic books, empathetic storytelling, and institutional support for artists and writers in Maeda 2026). When we judge Brevoort’s opinion solely on the merits of Marvel’s recent editorial decisions, it is true that the X-Men comics recently tried very hard to escape the frustrating stasis dictated by mainstream superhero narratives by establishing a radical new status quo, but after a while the bold (and equally divisive) storyline originally masterminded by Jonathan Hickman seemingly suffered a lack of editorial guidance and then reverted nonetheless to old, uninspired tropes (Johnston 2021; Meenan 2024).

Another blatant example of both the illusion of narrative change and the domestication of the once liberating postmodern approach into a standardised permutation matrix that rewards creative mediocrity and short-term gains, is the official Marvel announcement, dated 18 February 2025, of the resurrection of Earth 616-Gwen Stacy as a superpowered assassin, of all things (Anonymous 2025). Stacy is an important character not just for the Spider-Man lore but for the entire medium as well: she was Peter Parker’s first true love and her death was so groundbreaking when it was originally published in The Amazing Spider-Man #121 (June 1973) that historians of the medium argue it helped mark the end of the naïve, optimistic Silver Age of Comics and the beginning of the comparatively more realistic Bronze Age (Blumberg 2003). Even though death in mainstream comics has long since become a meaningless and transient inconvenience, today the problem is compounded by the absence of any real stakes within the current explosion of multiversal narratives and doppelgängers, of which the multimedia-spanning Spider-Verse is perhaps the best know contemporary example (cf. Kain 2023). For instance, in the limited series announced by Marvel (entitled The All-New, All-Deadly Gwenpool), Gwen Stacy appears as the clone of the original character who, once reanimated, adopts the codename “X-31” and engages with a heterogeneous ensemble of superheroes including Gwenpool – an unrelated, multidimensional, fourth-wall-breaking figure modeled after Deadpool.

The announcement for this series felt like the final straw. The news was so baffling that even mainstream industry-friendly outlets had to vent their anger via self-explanatory articles like “There Are Things We Want for Spider-Man, But Gwen Stacy’s Return Is Not One of Them” (Myrick 2025) or “Marvel Comics Is Doing The Unthinkable”, the latter sporting an unambiguous “What the F***?!” subtitle (Wilding 2025). Besides, Marvel’s announcement came after years of readers’ frustration at the editorially confusing (mis)management of Spider-Man and awkward, if not outright confrontational, interactions with the readers (fjmac 2023; Angeles 2024). One might question whether these examples genuinely qualify as the bold “new ideas and new stories that can serve as creative fodder for eventual film and animation development.”

Infinite crisis in the Spider-Verse

The heated reception of the new series prompted me to reflect on the state of the titles dedicated to Spider-Man, Marvel’s most prominent character and one of the most recognisable figures in contemporary popular culture. Although some readers may disagree, these books have been mired in editorial controversy since the publication of the much-debated storyline One More Day. Elaborated by then Marvel editor-in-chief Joe Quesada with the collaboration of screenwriter, novelist, and The Amazing Spider-Man writer J. M. Straczynski, along with a circle of collaborators (“[Brian Michael] Bendis, [Mark] Millar, [Jeph] Loeb, Tom Brevoort, Axel Alonso […], Ed Brubaker and Dan Slott”; Quesada in Weiland 2007b), One More Day was a 2007 crossover limited to the three Spider-Man titles then published by Marvel and specifically designed to kickstart a hard reboot of the company’s flagship superhero (Ginocchio 2017: 233-238). This goal was achieved by undoing Peter Parker’s marriage with Mary Jane Watson by way of a deal with Mephisto, the literal devil of the Marvel universe, to save the life of Parker’s elderly aunt May, who had narrowly escaped death before. As an added bonus, Mephisto would also erase from everybody’s memory Spider-Man’s secret identity, previously revealed during the Civil War limited series written by Millar and penciled by Steve McNiven. The result ended up being almost universally disliked by readers because of its messy plot and out-of-character decisions (see the “Reception” section of the Wikipedia entry for the storyline; cf. Reaves 2025 and Lennen 2023).

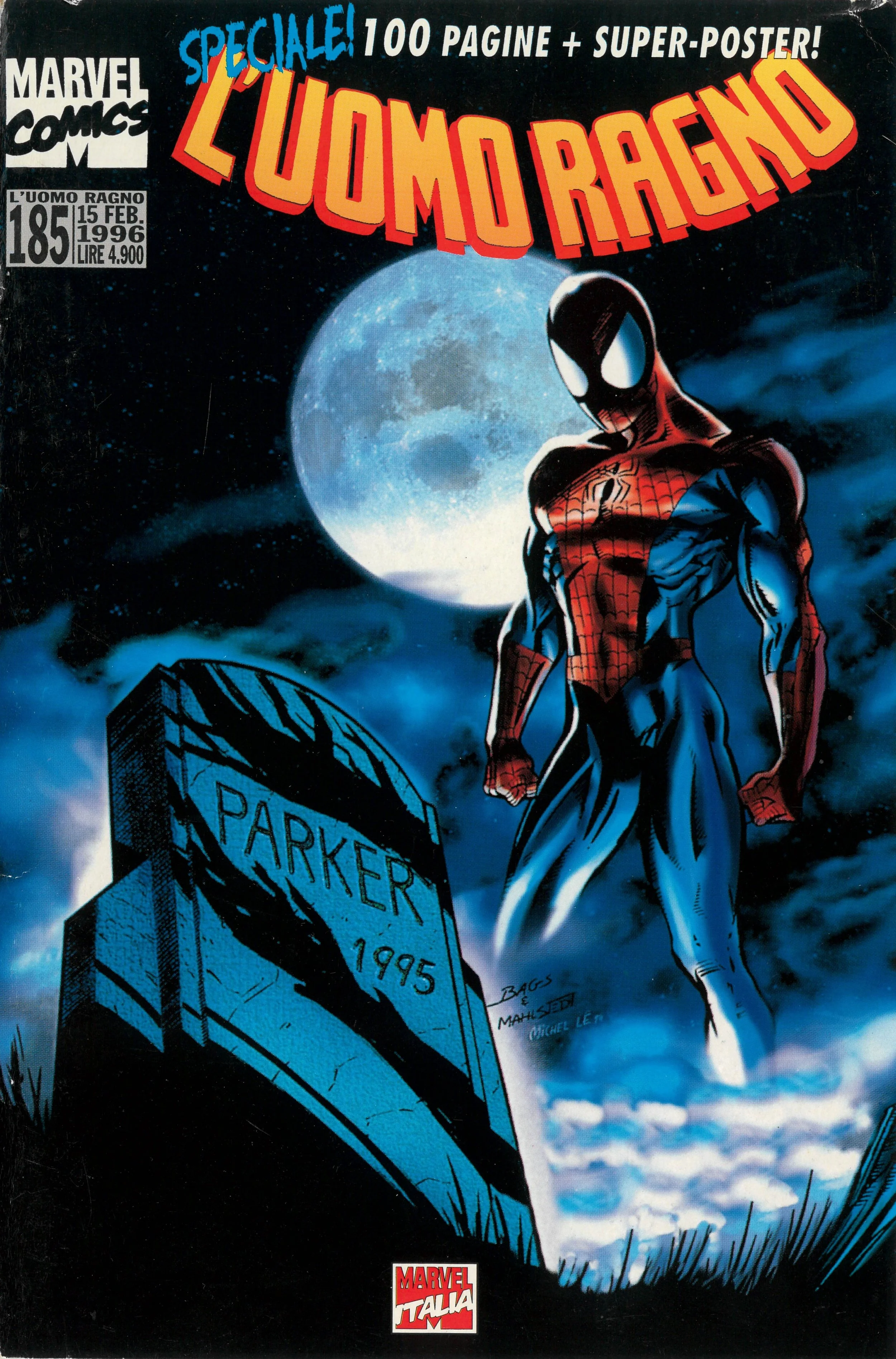

By contrast, the passing of time seems to have been particularly kind to the Second Clone Saga, which is usually considered “emblematic of Marvel’s problems in the 1990s” (see Danny Fingeroth’s comments in Veronese 2010: 77; for context see Sacks and Dallas 2020: 135; cf. Behbakht 2023; Lennen 2024; MNStash 2025). The subsequent revelations about the corporate drama unfolding behind the scenes helped clarify why and how certain misguided decisions were made (Goletz n.d.); at the same time, the publication of many lackluster storylines, failed reboots, and controversial retcons (resp., Ginocchio 2015; Ginocchio 2012), along with the equally exhausting and narratively bankrupt decades-long teasing of the dissolution of the One More Day status quo (e.g., Isaak 2021; see also Mendoza 2024), made many readers re-evaluate what were once considered unforgivable missteps (cf. Singer 2019: 74-94). In hindsight, the Second Clone Saga, which run from 1994 to 1996 and saw the unexpected return of the main protagonist’s clone from a half-forgotten 1970s story (i.e., the original Clone Saga), had its sincere and emotional moments of true wonder, sadness, and joy (e.g., Mary Jane announcing she was expecting a child to a jubilant but sick Peter in The Amazing Spider-Man #398), it was organically tied to the previous continuity while propelling the main cast of characters forward in their adult lives, it boasted a solid start and a coherent first act, and had at the very least a couple of issues that may well rank among the greatest in the history of the character (with J. M. DeMatteis, Mark Bagley, and Larry Mahlstedt’s The Amazing Spider-Man #400 probably taking the crown). In sum, as Douglas Wolk wrote, it was “a solid idea” that would have marked “a concrete and timely end to the third Spider-Man cycle”, whose defining feature was Peter Parker struggling with his identity and mental health against his various “shadow sel[ves]” and “nightmare id[s]” (like Venom, Carnage, and the Spider-Doppelganger) as he tried, mostly in vain, to overcome the loss of his parents (Wolk 2021: 93, 91; my emphasis).

L’Uomo Ragno #185: the first Italian edition of Amazing Spider-Man #400, which also included Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man #222, Web of Spider-Man vol 1 #123, and “The Cycle of Life” from The Spectacular Spider-Man Super Special (1995). Cover by Mark Bagley and Larry Mahlstedt. SOURCE: private collection. © 1996 Marvel.

A very short recap of what unfolded – including what was planned to unfold – across the four Spider-Man titles published at that time is in order. Already at his wit's end, suffering from PTSD, anxiety, and depression, and prone to meltdowns and upredictable outbursts of rage, a worn-out, solitary Peter Parker embarks on a soul-searching in an eerie “Philip K. Dick/Twilight Zone territory” that J.M. DeMatteis, writer of the Amazing Spider-Man at that time, summarised as a “twisted exploration of personal identity and a journey deep into the primal question, ‘who am I?’ What would a man do if he discovered that everything he believed about himself was a lie?” (DeMatteis from Veronese 2010: 74; cf. Sacks and Dallas 2020: 134, 174). This personal journey was intended to lead Peter Parker toward making peace with both his past mistakes and his present failures. Coping with the recent death of Aunt May would prove difficult, and even more destabilising would be the shattering revelation that he might in fact have been the clone all along (cf. DeMatteis in DeFalco 2004: 170). Nonetheless, the stage was set for Peter to step aside and allow Ben Reilly – the new identity assumed by the former clone during his years as a vagrant constantly on the road – to officially inherit the role of Spider-Man, while the former hero would retire with Mary Jane in anticipation of the birth of their first child, May Parker. As recalled by DeMatteis,

“we were going to send the Peter we knew and loved, the one who’d be revealed as the Clone, and Mary Jane off to have their baby, and they would live happily ever after. They would have this good life that I believe would have fully satisfied the readers. ‘With great powers comes great responsibility’, right? What greater responsibility is there than raising a child and teaching him or her to be a good and decent human being? I remember writing some dialogue for Aunt May about this very fact” (DeMatteis in DeFalco 2004: 171).

The bold story arc did indeed prove extremely popular and profitable in a time of financial distress for the company (Sacks and Dallas 2020: 135, 175). Because of this, its development was quickly derailed by the marketing department at Marvel, which insisted on an unreasonable extension of the original storyline; to make matters worse, the saga was further hampered by editorial indecision and infighting among different publishing divisions, leading to the departure of the original artistic teams who helped creating the storyline (cf. DeFalco 2004: 169-171, 180, 194; Sacks and Dallas 2020: 174, 208). The story was originally intended to run for roughly six months (three according to adjectiveless Spider-Man writer Howard Mackie, “a year at best” according to DeMatteis; Veronese 2010: 75); after more than two years of stalling and a mind-boggling sequence of twists, turns, and retcons that covered “twenty-two different story arcs and over 2300 comic pages” (which featured the return of both Aunt May and long-dead Spider-Man nemesis Norman Osborn, the disappearance of newborn May, and the death of Ben Reilly at the hands of the Green Goblin), disaffected readers left the titles in droves, and in the end the books lost almost half of their initial audience (Howe 2012: 365-366, 370, 372, 381-382; cit. from Sacks and Dallas 2020: 210). Ultimately, the Second Clone Saga failed only insofar as it was a victim of its own initial spectacular success.

Conversely, One More Day, with its brazen erasure of decades of the main character’s continuity, stands out right from the beginning as a jarring and disconnected narrative U-turn marred by plot holes that “nobody, including its creators, likes” (Wolk 2021: 95). Even more damningly, from the perspective of virtue ethics, the storyline doubled as a profound and unexplainable betrayal of Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson’s character traits and moral integrity, which understandably resulted in a general loss of faith in the editorial stewardship of the books:

“absent a life-altering event or a mind-blowing epiphany, we don’t expect fictional characters – or real people – to alter their deep-seated behavior abruptly and for no reason. Given the fantastical circumstances Peter Parker has faced throughout his career as Spider-Man, even the impending death of his aunt and a surprise offer from Mephisto don’t seem enough to trigger and justify such an about-face” (White 2012).

Unsurprisingly, the same opinion was shared by former Marvel editor-in-chief, co-plotter, and co-writer of the 1987 Amazing Spider-Man Annual where Peter and Mary Jane got married, Jim Shooter. In a comment published in late 2011 on his website, Shooter wrote:

“I finally got around to reading One More Day and A Brand New Day, and though I admire the skills of the creators I didn’t recognize any of the characters. Open note to Joe Quesada and the Marvel creative staff: If you don’t understand who the characters in your care are, call me and I’ll clue you in. Yes, that's a snarky comment. Yes, I’m that appalled by the thing” (Shooter 2011).

It is somewhat ironic that the entire One More Day storyline was designed to resolve the lingering issues that had plagued the Spider-Man-related titles since the implementation of top-down interferences and the retcons that affected the development of the Clone Saga more than a decade earlier. In both cases, the editorial mandate “allo[wed] the villain to get a permanent win over Spider-Man for no real reason aside from a business-oriented dislike of Peter's growth” and, once again, the elaboration of the plot caused friction with the main writer (Reaves 2025; cf. Sanderson 2008 and White 2012; see the Joe Quesada interview in CBR Staff 2008). Whatever one’s views on the qualitative merits of One More Day, the crossover appears to have been financially detrimental to the Spider-Man’s books: after an initial spike of interest fuelled by the controversy surrounding this story, sales steadily declined for Brand New Day, the immediate follow-up story arc. With only rare exceptions, sales volumes never actually recovered to the previous highs of the Clone Saga (see the tentative data gathered from Comichron and presented in Sartheking 2023).

The “strangest thing that Marvel has ever done”

In light of all this, the ongoing editorial refusal to undo the unpopular post-Clone Saga/Mephisto-sanctioned status quo arguably stands as one of the most striking examples of the sunk cost fallacy in contemporary entertainment industry, as Marvel’s editorial leadership remains unwilling to cut its losses after decades of financial and narrative investment (on the sunk cost fallacy see Chatfield 2018: 212, 282, 297). Nor is this the only instance of fallacious reasoning at work in the editorial logic of what Charlie Reaves has characterised as “the strangest thing that Marvel has ever done” (Reaves 2025).

Quesada repeatedly expressed his personal opposition to Peter Parker’s marriage, citing both a romanticised, nostalgic vision of the early Ditko, Romita, and Lee era of Spider-Man and corporate considerations, as exemplified by the following interview excerpts:

“The golden era of Spider-Man gave us things we had never seen in a comic before. […] When Peter Parker got married, it caused the character to be cut off from many of the social situations and settings that put him at conflict with his family, friends, and especially the girl he was dating. […] And whatever nerdish sex appeal he possessed, we had to tread very carefully. He became the perpetual ‘designated driver.’ Sure, Peter could hang around with other married folk – I bet that would be exciting! […] I’ll get personal, for a moment. I have an incredible marriage and a fantastic kid, but there is no question that my life was much more story-worthy when I was single. Was I happier? Absolutely not. Was my life a better story from a drama sense? Ummmm, yeah. It had many more twists and turns and theater and was a bit of a mess. […] Now let me say, not everyone, but for most: when people get married, they tend to settle down – life slows down and you gain different responsibilities, grown-up responsibilities, boring responsibilities. […] We all want Peter to catch a break and to settle down and have happiness in his life, but that isn’t really what we want. If that actually happened, people would stop caring about Spider-Man.” (Quesada in Weiland 2008).

“If Spidey grows old and dies off with our readership, then that's it[,] he’ll be done and gone, never to be enjoyed by future comic fans. If we keep Spidey rejuvenated and relatable to fans on the horizon, we can manage to do that and still keep him enjoyable to those that have been following his adventures for years. […] At the end of the day, my job is to keep these characters fresh and ready for every fan that walks through the door, while also planning for the future and hopefully an even larger fan base” (Quesada in Weiland 2007a).

Since an in-depth analysis of Quesada’s statements, along with other key excerpts from coeval interviews, would take too much space, I’ll limit myself to noting that his appeal to hypothetical future generations of readers (that is, today’s readers ) was tinged by rosy retrospection and special pleading and didn’t factor in cultural changes affecting societal norms (more on these points later). In addition, Quesada’s viewpoint presumed the perpetual corporate ownership of IPs despite the limits imposed by copyright laws, and maintained that an aging, mature character wouldn’t have the same appeal of a young one notwithstanding the fact that in our contemporary onlife cultural environment, where old and new contents simultaneously coexist in the digital sphere, young readers can be introduced to a long-established character via a collection of old stories or an adaptation from decades ago. Finally, by denying Peter Parker happiness and any lasting victories (professional, sentimental, or heroic), Quesada stunted the character’s growth and risked alienating the existing readership (again, more on this in later sections).

All things considered, in the absence of compelling in-universe justifications, the marriage needn’t be dismantled. Quesada didn’t actually offer any credible rationale as he proceeded to undo it anyway via a supernatural intervention – a choice regrettably uncharacteristic of the titles in question [3]. While it can be argued that some good and memorable stories were indeed published after One More Day, in the end none of them featured any new love interests the creators came up with for post-One More Day Peter Parker, which in hindsight invalidates Quesada’s primary motivations [4].

The “best Platonic ideal”

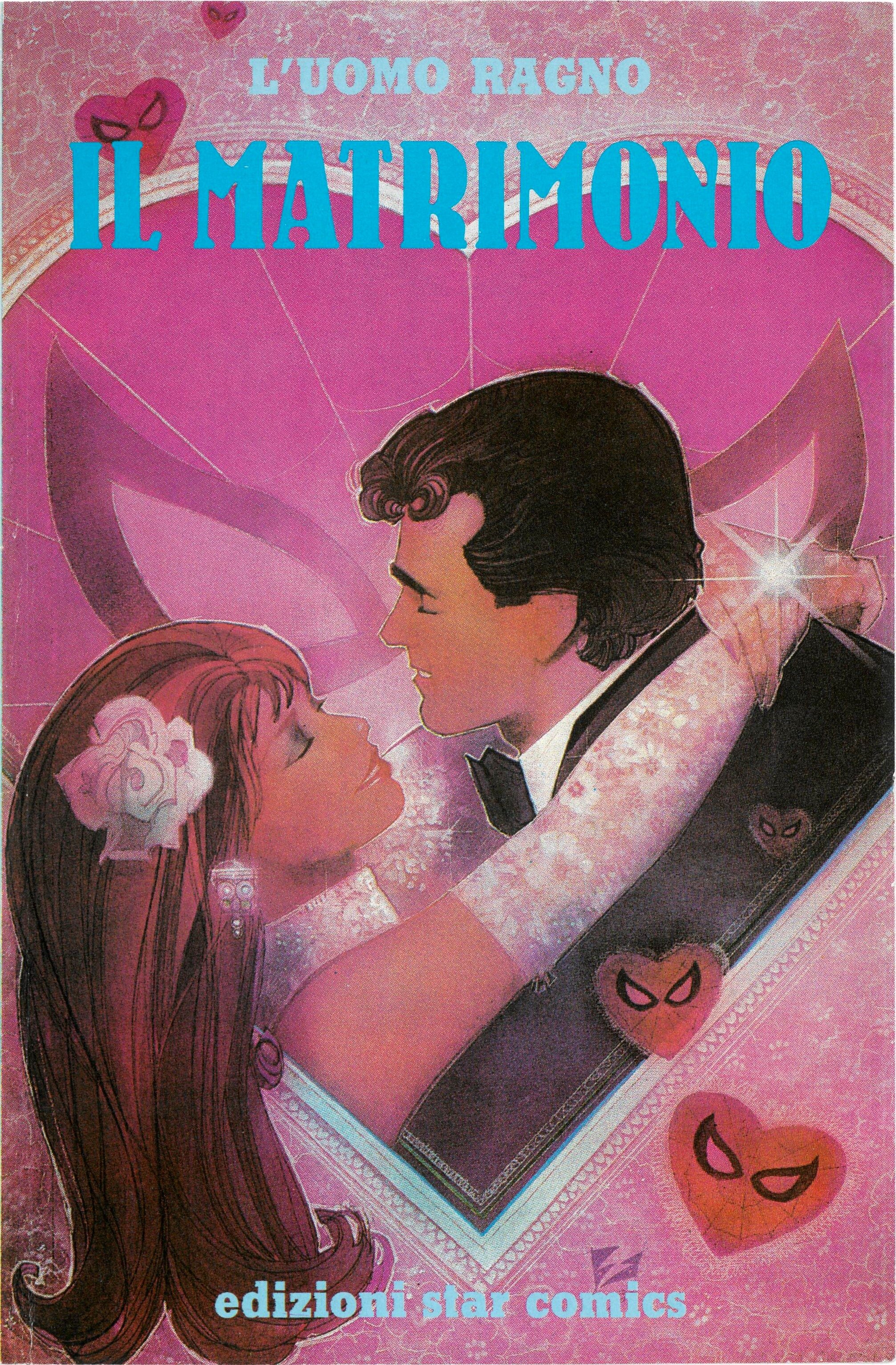

Definitely not the “best Platonic ideal” according to post-2000s Marvel editorship. Cover from the first Italian collected edition of The Amazing Spider-Man #290-292 and The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21: Speciale L’Uomo Ragno 2, Star Comics, 1991; variant cover by Bill Sienkiewicz. SOURCE: personal collection. © 1991 Marvel.

Although Quesada’s original master plan was meant to “rejuvenate” the character while preserving all prior events as canonical, it neither turned back the clock nor made Peter Parker younger. What it produced was instead an “infantilisation” of Spider-Man (Hart 2021): a fully-grown character trapped in a Groudhog Day-like limbo as an emotionally immature kidult who repudiates his “greatest responsibility”, as Aunt May puts it in J. M. DeMatteis & Bagley’s The Amazing Spider-Man #400 – namely, being a husband and a father. Post-One More Day Spider-Man becomes the poster child for Peter Pan syndrome or, in old-school analytical psychology parlance, a narcissistic puer æternus unable to come to terms with ageing. (Cue the obligatory Millennial meme of Steve Buscemi’s ‘How do you do, fellow kids?’ sketch.).

Former Marvel Comics editor-in-chief and writer Tom DeFalco stated that such outcomes are the inevitable results of the readers’ alleged preference for a perennial reversal to the status quo in vogue during their childhood. The “simple truth of comic book readers” would be that they “don’t like change”, DeFalco declared, adding that “[t]hey claim they like change but they always [want] everything back to the way it was when they were kids” (DeFalco in Singer 2019: 94). A qualitative examination of this statement is beyond the purview of this post; suffice it to note here that DeFalco himself had relinquished his editorship in 1994 while contributing to the Clone Saga because of irreconcilable disagreements with Marvel management (Sacks and Dallas 2020: 133-134). This episode, rather than indicating an extraordinary cognitive dissonance experienced by large swathes of the fandom, exemplifies the negative impact of punishing or ineffective editorial restructuring and top-down interference on creators.

Indeed, the success of inter- and multigenerational narratives in autobiographical graphic novels and decades-long mangas (and animes) demonstrates that readers are, in fact, eager to embrace long-term narrative evolution, character growth, and definitive conclusions. Despite occasional backpedaling, this was also, by and large, the real selling point and the raison d’être of the whole Marvel universe until the early 1990s. In 1991, former Star Comics editor-in-chief, former CEO of Marvel Comics Italia, and current publishing director of Panini Marco Marcello Lupoi singled out Spider-Man as the clearest example of the classic Marvel approach to comic book storytelling:

“In the comic-book universe created by Stan Lee, one defining feature above all helps make superheroes seem like real people: change. […] A clear example of this approach is the career of Spider-Man, a.k.a. Peter Parker. When he first appeared in 1962, the world-famous web-slinger was a bespectacled teenager, a bookworm in his final year at Midtown High School. However, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, his brilliant creators, understood that this was meant to be only an initial phase. Spider-Man would age alongside his readers, through a process of change that was slow, gradual, and inevitable [, ultimately leading to his marriage]” (Lupoi 1991; original emphasis; my translation) [5].

Four years later, Lupoi introduced the new Clone Saga to Italian readers and explicitly contrasted the evolving Marvel universe with static European narrative dynamics:

“Something new is on the horizon for Spider-Man. Comebacks, deaths, new villains, new creative teams. Marvel has decided to take the Wall-Crawler and his entire world and turn them upside down, dramatically altering a status quo that had essentially remained the same for years, specifically ever since our hero married Mary Jane Watson. The reason behind this urge for ‘revolution’ will likely be lost on many of you. Italian readers are famously conservative. Once a character settles into a well-defined mold, we would like to see it crystallized that way forever. A Diabolik driving the same car. A Tex with the same friends and enemies. A Dylan Dog wearing the same clothes, the same supporting cast, the same narrative dynamics. While American soap operas reinvent themselves season after season, mainstream audiences here tend to prefer shows like Derrick, built on the same identical situation endlessly repeating week after week. It goes without saying that Marvel comics operate on the exact opposite philosophy: change. Spider-Man graduates from high school, goes to college, loses friends, girlfriends, enemies; he gets married, moves house, changes jobs, changes his costume. His life is a whirlwind of personal evolution, and anyone who has been following his adventures for a while knows this perfectly well […].” (Lupoi 1995; my translation) [6].

Whether that was really the creators’ original plan is beyond the point; in this case, what’s important is the cumulative result of their foundational decisions (along with those made by their colleagues and successors) on the emic, in-universe Marvel narrative progression. As former Marvel editor, writer, and biographer Danny Fingeroth summarised, while the stories published by DC Comics until the 1960s showed “little if any forward character growth or development of the various situations in that universe”, Marvel’s entire narrative strategy hinged on the idea that its characters did actually

“develop over time. They changed and grew from issue to issue, year to year. Lee and his collaborator were incrementally creating some form of literature. […] Marvel’s stories and everything surrounding them were evolving, subtly inviting readers to grow, too. This was a large part of what made Marvel so irresistible to those on its wavelength. And there were more and more people on its wavelength all the time” (Fingeroth 200: 136, 138; original emphasis).

The adoption of serialised storytelling and the “lengthening of the story lines” allowed for “stories, subplots, and especially characters” to be “developed as never before” in a way that started to resemble, if not real lives, at the very least “lives as portrayed by creators of novels and plays and movies that dealt with human growth and development” (Fingeroth 2019: 136; my emphasis) [7]. The result of all the characters growing together was an unprecedent, coherent, and tightly woven in-universe continuity that set the company apart from its mainstream competitors – an “epic among epics, Marcel Proust times Doris Lessing times Robert Altman to the power of the Mahābhārata” (Wolk 2021: 4) [8].

In 2025, however, Brevoort, who was part of the editorial team that elaborated the One More Day storyline (Weiland 2007b), confirmed that the post-One More Day status quo is here to stay: “I believe that we’ve concluded decisively that the best platonic ideal of Spider-Man is one that is unattached [i.e., unmarried], and that conclusion isn’t going to be changed by a particular alternate interpretation momentarily performing well” (scil., Ultimate Spider-Man, which is the current alternative-universe title by Jonathan Hickman, Marco Checchetto, and David Messina in which Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson are married with kids; cit. from Brevoort 2025b; cf. also Brevoort 2025c). From a narrative perspective, this “Platonic ideal” ignores Marvel Comics’ once “defining feature” and replicates Quesada’s suggestion that an out-of-character deal with the devil is preferable to a divorce between responsible and consenting adults (“Sorry, divorce is out, but Faustian bargains are cool!”, from White 2012: 238; see Weiland 2007b for Quesada’s false dichotomy). Besides, the editorially preferred “unattached” status of an infantilised Peter Parker is problematic for another reason. According to novelist, comic book writer, and chaos magician Grant Morrison,

“in a secular, scientific rational culture lacking in any convincing spiritual leadership, superhero stories speak loudly and boldly to our greatest fears, deepest longings, and highest aspirations […] and the best superhero stories deal directly with mythic elements of human experience that we can all relate to, in ways that are imaginative, funny, and provocative. […] At their best, they help us to confront and resolve even the deepest existential crises. We should listen to what they have to tell us” (Morrison 2011: xvii).

What do twenty years of meandering stories about an emotionally immature Peter Parker in his mid-twenties or early-thirties have to tell us? Even if unintentionally, the editorial rationale invoked to defend the hedonistic superficiality of his romantic relationships and the apparent disposability of his new love interests not only fell short of providing any higher mythical aspiration; they also are a fossil of the mysoginistic ‘lad culture’ that characterised the early 2000s, “arguably suggesting that the marriage wasn’t a positive development, that MJ was an inessential character, and even that the heroic male is better off alone” (Sanderson 2008; on lad culture and the early 2000s see Coslett 2023). I can hardly imagine a worse betrayal of a character whose entire arc was originally built on the credo: “With great power, there must also come – great responsibility!”.

The “essential quality of a legend”

By the time Quesada issued his blank-slate directive, it was already far too late to carry it out as intended. During his stint as a writer on The Amazing Spider-Man between 1978 and 1980, Marv Wolfman had already acquiesced to the editorial decision “to make Peter older for some reason”, but “planned to put him in graduate school, and just leave him there. I didn’t like the idea of letting him get married or have kids.” As he explained in 2004, “if [Peter Parker’s] still fouling up as an adult, he just isn’t a hero anymore. He’s pathetic” (Wolfman in DeFalco 2004: 78; my emphasis). While Wolfman’s premise, much like Quesada’s, is questionable (did Ulysses’ wanderings, mistakes, marriage, and family truly render him pathetic and unrelatable as a hero?), his reasoning is nonetheless sound: once a character has matured and accumulated a sequence of formative life events, any abrupt or insufficiently motivated return to a prior status quo risks becoming narratively self-defeating (the reasons are explained below). Perhaps more importantly, the stakes and tropes that define superhero narratives are, by their very nature, radically different from those typical of any other genre within the same medium. As Morrison has pointed out, they are closer to religious narratives than to conventional serial fiction. They are almost myths.

In his brilliantly controversial, and ultimately rejected, synopsis for the DC Comics crossover Twilight of the Superheroes, Alan Moore considered “how one of the things that prevents superhero stories from ever attaining the status of true modern myths or legends is that they are open ended. An essential quality of a legend is that the events in it are clearly defined in time” (Moore 1987; on myth and comics see Curtis 2019). In his pitch, Moore reasoned that because (post-)Bronze Age superheroes storylines were chained to the “commercial demands of a continuing series” in which nothing could ever change or evolve permanently (a trope that primarily affected DC characters, as we have seen), such stories

“can never have a resolution. Indeed, they find it difficult to embrace any of the changes in life that the passage of time brings about for these very same reasons, making them finally less than fully human as well as falling far short of true myth” (Moore 1987; my emphasis).

Myth, however – and especially oral mythology – cognitively reproduces itself by generating variants, and this generation accounts for the existence of different versions of the same story, sometimes complementary and mutually enriching, though at other times diametrically opposed and contradictory: the myth of one character “contains all the variants”, and for those myths whose origins are lost in time, continuously retold by different storytellers with different agendas, no single variant can be proclaimed to be “the ‘true’ version of the [same] myth” (Powell 2021: 5). This does not mean that every literary variant has the same cultural weight, cognitive grip, or memorability, nor does it mean that a character’s fictitious biography can go on indefinitely with unexplained and increasingly incoherent twists, turns, and retcons: the internal structural coherence of each variant is paramount for its survival and transmission. Incidentally, this is the crucial point missed by the mid-1990s marketing department at Marvel and by the new editors a decade later: we intuitively and effortlessly represent the fictional characters’ motivations, desires, and emotions in our minds as if they were real agents, and we use those mental representations to predict and assess the characters’ actions and demeanour as a consequence of their personality traits. The same goes for the coherence of the fictional worlds they inhabit. In both cases, inconsistency is usually rejected by the audience or the readers (Sanchez-Davies 2016: 54-55; fictional characters are given a bit more cognitive leeway in this regard; see Fillik and Leuthold 2013; cf. also Dubourg and Baumard 2022).

Remarkably, the authors behind serialised superhero comic books intuitively elaborated or adopted the same narratological precepts and included them into their own storytelling/commercial framework, developing main universes and following their characters’ vicissitudes while deploying alternative, mythical retellings set on infinite Earths as “counterfactual […] storyworlds” or “what ifs… ?” (Ayres 2021: 44, based on Kukkonen 2010: 55; for Moore’s role in the reimagining and systemisation of Bronze Age multiverses see Ayres 2021: 42). As we have seen, this clever solution would eventually backfire with the proliferation of multiversal backdoors making every key turning point moot and inconsequential, but when Moore was pitching his proposal this was still a relatively novel and promising concept. Something crucial was missing, though, as Moore was quick to point out: in the long run, the biographical open-endedness of each comic book character in each storyworld – especially those considered as the main versions in their prime universe – was not sustainable.

Interestingly, Twilight of the Superheroes was also meant to offer a meta-commentary on DC’s canonical continuity in the wake of Wolfman and George Pérez’s epoch-making crossover Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985-1986). As recently noted by Jackson Ayres,

“[t]he broader point made in the Twilight proposal […] is that when established narrative histories are invalidated – an editorial move that also implicitly invalidates the creative labor responsible for producing that history – serialized comics lose the crucial ability to engage productively with their past” (Ayres 2021: 71).

Once seen through Moore’s lenses, the part of the Second Clone Saga that roughly followed the publication of The Amazing Spider-Man #400 and the radical retcon provided by One More Day managed in one fell swoop to both prevent the natural character progression of 1990s Peter Parker/Spider-Man towards his final resolution as a character (with his mythical twin Ben Reilly rising to the occasion and the Parkers’ daughter May as heir apparent) and invalidate decades of “established narrative histories”. No wonder that the current Amazing Spider-Man’s storylines are met with either cold feet or widespread indignation: they have lost the “crucial ability to engage productively with their past”.

As if such insights were not enough, in 1983 Moore had already singled out the narratively crippling stasis suffered by Peter Parker/Spider-Man as an adolescent, immature character who “has a lot of trouble with his girlfriends” to denounce the fact that sometimes in the mid-1970s Marvel’s storylines had “ground to a halt” and “stopped developing” (more strikingly, Moore published his critical notes in an official Marvel UK magazine; Moore 1983). Even though subsequent runs on The Amazing Spider-Man and The Spectacular Spider-Man invalidated Moore’s initial analysis (as they slowly and organically integrated more adult and mature themes, including Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson getting married and expecting a child, possibly influenced by the industry-wide reception of Moore’s own revolutionary approach to comic books), the One More Day’s blank slate, which featured the uncalled-for return to a perpetually post-adolescent, immature Parker who “has a lot of trouble with his girlfriends”, proved Moore’s assessment eerily prescient [9]. Beware the magic of the Northampton Bard.

Of mice and spiders

One More Day deliberately froze the flagship character of the company in a state of arrested development – much like an old-fashioned comic strip figure – in order to dilute his complicated history, erase his personal growth, and maximise his appeal as a purely commercial mascot. Regardless of any original creative intent, the One More Day retcon anticipated the corporate strategy that would be further entrenched following Disney’s acquisition of Marvel in 2009 (for a detailed financial history of the tumultuous period that followed Marvel’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy and subsequent merger with Isaac Perlmutter’s Toy Biz in 1996, see Howe 2012: 379-432; cf. Shooter 2025 [1998]). In practice, Peter Parker, the married-with-child character who had to fail, suffer unspeakable losses, and face his own personal demons before accepting his greatest responsibility, had been subjected to a process of Disneyfication, which is defined in the Cambridge Dictionary as “changing something so that it entertains or is attractive in a safe and controlled way” (Cambridge Dictionary n.d.; see Bryman 2004: 5: “To Disneify means to translate or transform an object [or, in this case, a character. My note] into something superficial and even simplistic”).

It is somewhat ironic, then, that Panini Comics, the Italian licensee of the Disney characters acquired by Marvel during the ultimately financially counterproductive buying spree of 1991, has recently found renewed critical and commercial success with its flagship weekly title Topolino (lit., “Mickey Mouse”) under the direction of new editor-in-chief Alex Bertani. Early in his tenure, Bertani introduced traditional Marvel-style continuity rules, emphasised fictional worldbuilding through crossovers, encouraged more emotionally complex storytelling involving the core characters of Duckburg and Mouseton, and, last but not least, greenlighted a flurry of marketing gimmicks (Brambilla 2022; for a recent assessment see Fiamma 2026). This shift, which built on the successes and editorial transformations achieved under former editor-in-chief Valentina De Poli (De Poli 2022), is perhaps unsurprising, given that Bertani began his career in the comic industry in 1994 when he joined the marketing department of Marvel Italia, then the Italian subsidiary of Marvel USA.

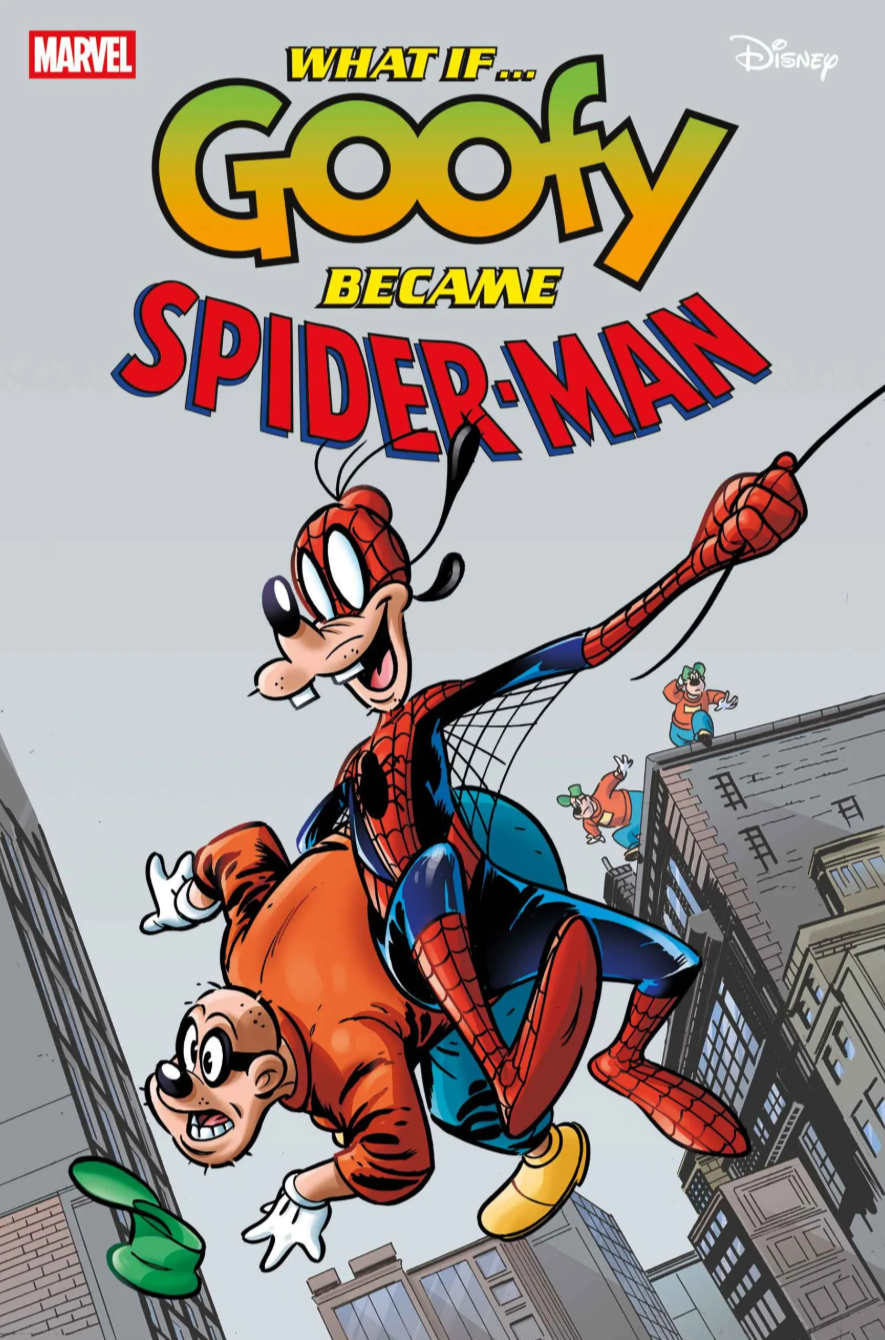

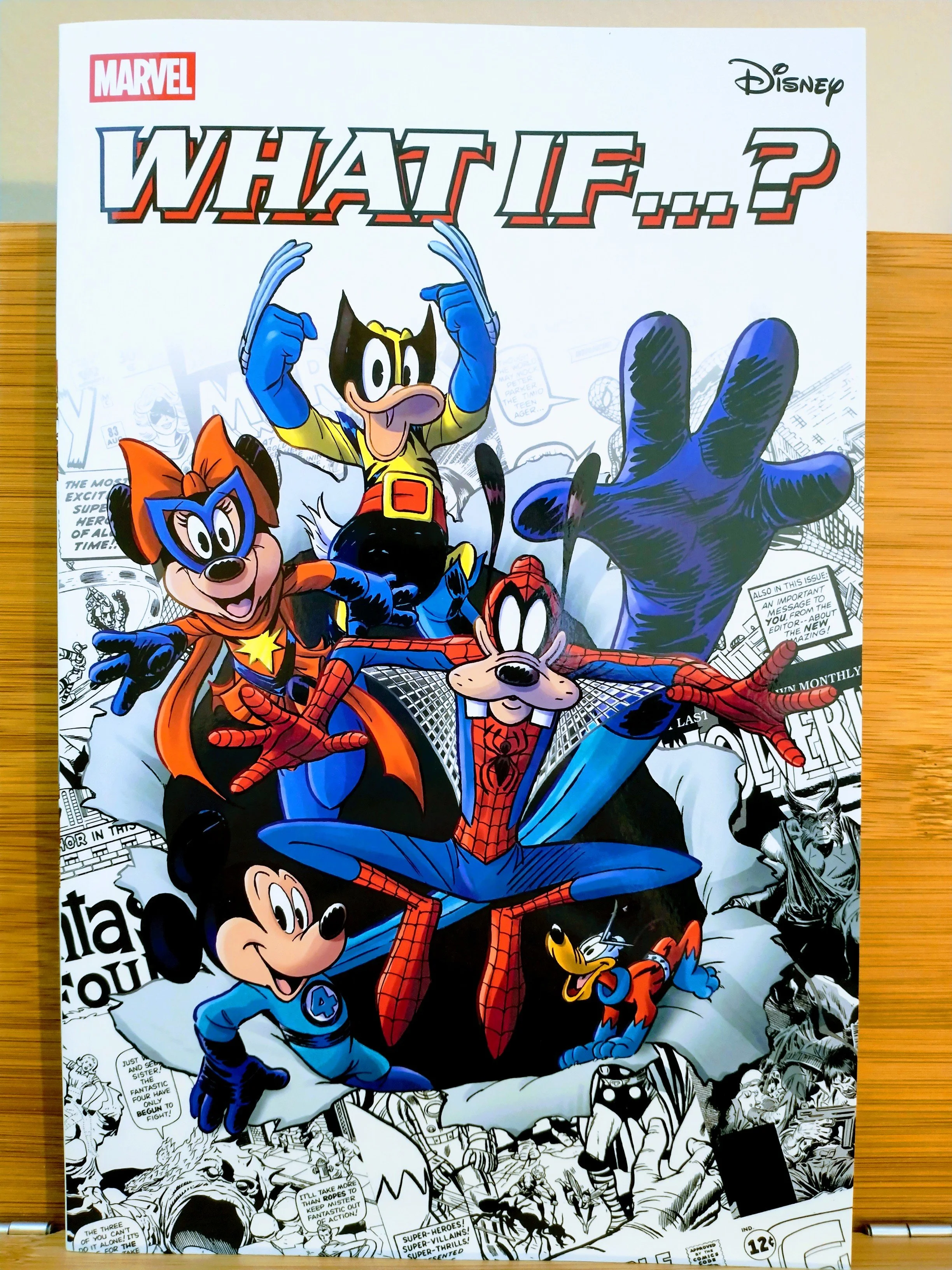

However, as exemplified by a peculiar and recent joint project, the tension between the two different approaches may produce lackluster results. Between 2024 and 2025, Marvel published a series of “What If… ?” one-shots co-produced with the collaboration of a stellar roster of Italian Disney writers and artists, all under the supervision and strict narrative control of the American company. These issues featured familiar Disney characters taking on the roles of iconic Marvel superheroes: Goofy turns into Spider-Man (and Hulk), Donald Duck becomes Iron Man (and Thor), Minnie Mouse dons the Captain Marvel insignia, and Mickey Mouse is reimagined as Mr. Fantastic and Iron Man (again). While the art, courtesy of seasoned veterans like Giada Perissinotto, Alessandro Pastrovicchio, and Donald Soffritti, truly shined, the narrative beats and tropes felt relatively stiff, unemotional, disjointed, uninspired, and even unfunny by European standards. Disneyfied, if you will (see Fiamma 2024a; Fiamma 2024b; Pavan 2024; Nocera 2025; Santarelli 2025; Fidecaro 2025).

The US trade paperback edition of Marvel & Disney: What If… ?. Cover by Andrea Freccero and Lucio Ruvidotti. SOURCE: private collection. © 2025 Disney/Marvel.

As strange as it may sound, however, the Disneyfication of a Disney product wasn’t always the inevitable outcome it seems today. Once upon a time, Disney earned its true acclaim through authentic, raw emotions and relatively complex, dramatic events that connected with the audience at large, regardless of their age. That is not longer the case. With regards to the “What If… ?” collaboration, the overly cautious limitations and sanitised narrative constraints imposed by the parent company, as articulated by Steve Behling (who authored the plots for all but one of the one-shots), can be inferred by reading between the lines of a short interview published in the Italian edition of the Spider-Goofy issue. Concerning the decision to portray Uncle Ben as a sidecar (!?) and to reframe his death as an economic issue (selling the sidecar would help relieve Aunt Tessie’s financial duress), writer Riccardo Secchi remarks with barely concealed dissatisfaction:

“The question of how to adapt the tragic event of Uncle Ben’s death, which serves as the motivation for Peter Parker to take up the role of a superhero, was definitely not an easy one. Obviously, it was not possible to reproduce such a dramatic event, even though the Disney universe has actually never shied away from depicting tragic aspects of existence, at least in animation. One only has to think of Bambi or Dumbo, for example” (What If… ? Pippo diventa Spider-Man: 32; my translation).

Secchi further notes that the situation may be somewhat different in the comics medium (What If… ? Pippo diventa Spider-Man: 32); however, internationally renowned masterpieces such as Don Rosa’s Eisner Award-winning series The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck, along with innumerable stories from both the Italian and broader Disney comics traditions, in which characters evolve, mature, and confront emotionally complex situations, openly contradict these claims, which appear to be understandably diplomatic in nature (cf. Del Core 2023: 240, 245, 255, 267, 271).

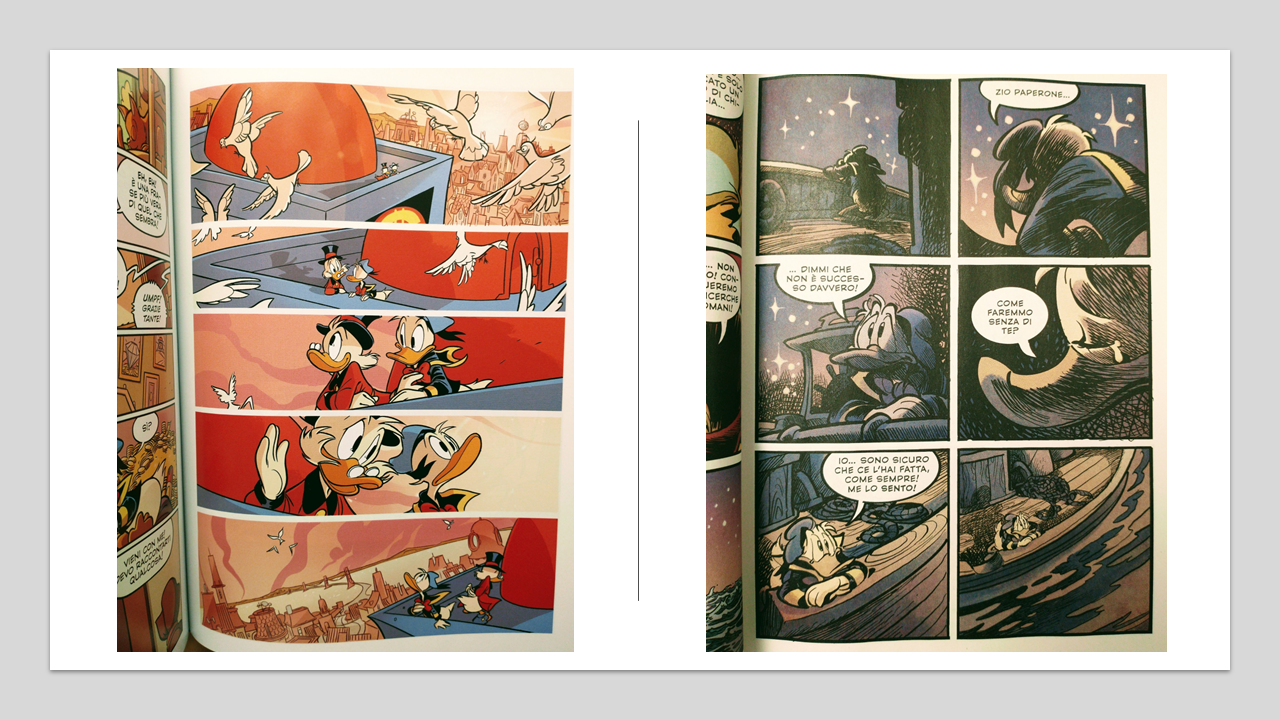

Two emotional vignette (panels) from the recent Italian Disney production: Paperino (Donald Duck) longing for a lost and impossible love (left), and mourning the disappearance and possible death of a family member (right). SOURCES: (left) Alex Bertani, Vito Stabile, and Stefano Zanchi. 2022. L’ultima avventura di Reginella. Topolino Extra - Graphic Novel 12i. Modena: Panini Comics, p. 27 (originally published in Topolino #3430, 18 August 2021); (right) Fabio Celoni (colours by Alessandra Amorotti and Luca Merli; colour supervision by F. Celoni), “Paperone in Atlantide”, in Topolino #3661, 21 January 2026, p. 35. SOURCE: private collection. © 2025 Disney/Panini Comics.

From a historiographical perspective, it is only fair to note that Disney lost any genuine interest in, and emotional connection to, its comic book division long ago. In its homeland, Donald Duck, and even more so Mickey Mouse, is reduced to a brand mascot, an icon; elsewhere, he is a fully-fledged, almost mythical character who, despite some obvious limitations, is able to feel, laugh, cry, grow, live, and, sometimes, even learn from its mistakes (De Poli 2022: 233; cf. Del Core 2022). Today, the US production of comic books featuring the company’s flagship characters is negligible and largely outsourced to brand licensees. Considering that until a few years ago the internationally renowned Italian production accounted for roughly 70% of all Disney comic books worldwide (De Poli 2022: 89), and that in 2012 the Italian readership of Topolino comprised approximately 1,114,000 adult readers and 600,000 children – figures which, despite a shrinking market, remain relatively strong even today (De Poli 2022: 186; Fiamma 2025) – the situation should, at minimum, have been reversed, with Italian authors plotting stories for their US counterparts, if not being given completely carte blanche.

Conclusion

In his The Self-Tormentor, Latin playwright Terence, who lived in the 2nd century BCE, famously wrote: “I am a human being, and nothing that is human is alien to me”. Emotional and intellectual respect for all readers through multi-layered, emotionally engaging, and intelligent storytelling that neither talks down to its audience nor dumbs down its plots, while remaining true to the characters and their history and appealing to everyone – that’s an art honed by many Italian Disney writers and artists (see De Poli 2022). This winning formula was patiently and carefully crafted over more than ninety years of Topolino’s almost uninterrupted editorial existence – an almost alchemical distillation resulting from the hard work and trusting collaboration of generations of talented artists and writers pushing the envelope, smart editors ready to take the lead, and a multigenerational, perceptive readership. Trust is fragile, though, and once it is broken, for whatever reason, it is very difficult to restore it. As sales diminish and readership, artists, and writers pivot away, editorial skills and sensibilities wither away too. This may sound banal, but this is something the US company seem to have forgotten. The impact on its subsidiary is obvious.

Directives issued from the upper levels of the Disney corporate hierarchy have already brought Marvel Studios to the brink of an irreversible financial and creative crisis (Fritz 2025). The comic book division by itself does not generate enough profit to justify its existence within a major corporation, and “the recent rise in comic book-based films has had little to no effect on comic book sales within the American market” (Hionis and Ki 2019). The recent launch of more or less radically reimagined alternative universes (Marvel’s Ultimate and, most notably, DC’s Absolute lines) has enjoyed significant critical and commercial success; however, the situation reportedly remains financially and creatively worse for Marvel Comics (cf. MacDonald 2025c). The case study of Spider-Man presented above underscores that the roots of this failure to reverse course run deep. Without a change of leadership and strategic planning at both the business and editorial levels, it is not an unlikely scenario that Disney may ultimately license out the rights to and management of Marvel titles and characters, as it has already done with his own historical in-house IPs. From an investment standpoint, the worst-possible outcome would be a repetition of the mistake made with another well-known property. As I wrote some years ago in a peer-reviewed article, “in 2001, Disney bought the rights to produce the Power Rangers TV series following the buyout of Fox Family Worldwide for $5.3 billion. In 2010, because of the corporate failure to manage the franchise, original developer Saban bought back the rights of Power Rangers from Disney for $65 million (James 2017)” (Ambasciano 2021: 256-257). Yet one must ask: from a creative perspective, would such developments ultimately be bad things at all?

Perhaps the most thrilling What If…? scenario is still to come: What if Marvel Comics, as we know it, folded… and someone from the Italian Disney/Panini Comics’ editorial board past and present, like De Poli, took over? Now, that’s a counterfactual crossover I would really love to read.

Notes

This post first appeared here on 10 March 2025, and was later shortened, revised, and (hopefully) improved between April and August. The article was subsequently expanded and amended on 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 January, and 6, 7, 11, 16, and 20 February 2026.

[1] “If a bard were to place not a curse upon you, but a satire, that could destroy you. If it was a clever satire, it might not just destroy you in the eyes of your associates, it would destroy you in the eyes of your family. It would destroy you in your own eyes. And if it was an extremely finely worded and clever satire, that might survive and be remembered for decades, even centuries. Then years after you were dead, people still might be reading it, and laughing at you, your wretchedness, and absurdity” (from Moore 2003).

[2] I’ve recently come across a post by a comic book shop owner that aptly summarises other relevant issues here: “price, decompression, constant events, oversaturation, and writers not staying on books for more than a year makes it harder to want to buy single issues. [Comic books are] [e]xpensive, [there are] too many events, too many entangled stories, [and] not enough actual stories per issue” [Anonymous 2024]. Another contributing factor affecting the quality of the stories itself might be the diffusion of storytelling handbooks and the proliferation of courses and classes about creative writing over the course of the last decades, which standardised and popularised certain narrative techniques to the detriment of other out-of-the-box approaches and choked the unorganised, but lively, creative effervescence experience by the industry in the second half of the 20th century (for an analysis of the widespread diffusion of the hero’s journey in Hollywood see Ambasciano 2021; on the creative explosion that characterised mainstream US comic books in the 1970s see Mazur & Danner 2014: 45-60).

[3] A sequence of fallacies and biases concerning One More Day, along with Quesada’s reasoning to undo Peter and Mary Jane’s marriage regardless of the implications for the history of both the characters involved and the books themselves, is available in Sanderson 2008; see also White 2012; for a contrastive intergenerational analysis focussed on divorce rates, the developmental impact of failing marriages and divorces on attachment, and changing views on marriage that may help contextualise the early-2000s Marvel editorship’s aversion to Peter Parker’s marriage see Crowell, Treboux, and Brockmeyer 2009; Kennedy and Ruggles 2014; Di Nallo and Oesch 2023; Bowens 2025.

[4] “It’s the strangest thing that Marvel has ever done: the publisher took a character who seemed to have unstoppable momentum and simply removed all of his progress and trapped him in a static state for no benefit at all. There haven’t been any amazing groundbreaking stories told because Peter and Mary Jane aren’t together. It didn’t push his character further in any way; it didn’t teach him a lesson about responsibility, because he doesn’t even remember having been married to Mary Jane to begin with” (Reaves 2025).

[5] The passage continues as follows: “Accordingly, in 1965 Peter graduates from high school and enrolls at university a few months later. The four years he spends at Empire State University unfold over thirteen years in real time, with his graduation taking place in October 1977. This is followed by a period of doctoral study and, after leaving academia, another major turning point in 1987 – his marriage” (Lupoi 1991; my translation).

[6] Here’s the rest of the excerpt: “Now, however, we are about to face changes so radical that they will overturn everything we know about Peter Parker and his world. Some will frown. Others will cry scandal. Let me explain what lies behind the revolution that is about to erupt. In America, in recent years, media attention (and the public’s) has been monopolized by major events within comic-book stories. The death of Superman. The transformation of Green Lantern into a super-criminal. The crippling of Batman and his replacement by a ruthless vigilante. At DC Comics (Marvel’s traditional rival), writers have pulled no punches and, month after month, have regained the readers’ lost favour through unprecedented narrative upheavals. Purists complained, traditionalists tore their hair out, but struggling titles suddenly soared back to the top of the sales charts […]. For a long time, Marvel attempted to ignore this trend, partly out of a certain snobbery toward rival DC. […] Then, over time, something changed. Faced with a U.S. market in deep crisis (in both sales and ideas), Marvel too sat down at the table and asked itself: ‘How can we breathe new life into our heroes? How can we renew them, propel them into the 1990s?’ […]. If you stay with us, you will see new adversaries, new developments, and the most incredible and mind-bending sequence in the entire career of Spider-Man. Don’t believe it? Just wait and see…” [Lupoi 1995; original emphasis; my translation].

[7] A strong editorial strategy supporting long-running story arcs, evolving characters, and proper endings may lead to best-selling collected editions long after the series have ended, cementing their status as ‘classics,’ particularly when their quality is above average (see Lippi in Tosti 2016: 779, 781-782). On the contrary, change is rejected when it is poorly conceived, cheaply developed, badly executed, subjected to interference, and then – following the inevitable backlash from the target readership – reverted to the wrong status quo ante due to corporate incompetence or editorial unwillingness to pinpoint why such a flawed change was rejected in the first place.

[8] This is a time as good as any to recall that Marvel characters also stood out from the competition because they “had flaws – hell, embodied flaws, weaknesses, vulnerabilities – of personality. You could find their diagnoses throughout the various edition of a psychiatrist’s DSM diagnostic handbook. They had tragic pasts that they actually acknowledged, reflected on, and were motivated by” (Fingeroth 2019: 134; original emphasis).

[9] In Moore’s own words: “[w]e were wild-eyed fanatics to rival the loopiest thugee cultist or member of the Manson family. We were True Believers [Stan Lee used to call Marvel faithful readers and aficionados “True Believers”. My note]. The worst thing was that everything had ground to a halt. The books had stopped developing. If you take a look at a current Spiderman [sic] comic, you’ll find that he’s maybe twenty years old, he worries a lot about what’s right and what’s wrong, and he has a lot of trouble with his girlfriends. Do you know what Spiderman [sic] was doing fifteen years ago? Well, he was about nineteen years old, he worried a lot about what was right and what was wrong, and he had a lot of trouble with his girlfriends” (Moore 1983: 47).

Refs.

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2021. “The Trials and Tribulations of Luke Skywalker: How The Walt Disney Co. and Lucasfilm Have Failed to Confront Joseph Campbell’s Troublesome Legacy.” Implicit Religion 23(3): 251-276. https://doi.org/10.1558/imre.43229

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2023. “Alan Moore racconta i supereroi tra populismo e nostalgie infantili. Il lato oscuro del fumetto made in Usa.” Review of Alan Moore, Illuminations, London & New York: Bloomsbury. L’Indice dei Libri del Mese 40 (11): 11. https://www.lindiceonline.com/l-indice/sommario/novembre-2023/

Ambasciano, Leonardo. 2024. “Hollywood brucia. Declino e caduta dell’impero di celluloide tra scioperi, scandali e intelligenza artificiale.” Review of Ryan, M. (2023). Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood (New York and Boston: Mariner Books). L’Indice dei Libri del Mese 41(1): 16. https://www.lindiceonline.com/l-indice/sommario/gennaio-2024/

Angeles, Christian. 2024. “NYCC ’24: Spider-Man and His Venomous Friends Panel Ends with Awkward Silence.” Comics Beat, 21 October. https://www.comicsbeat.com/nycc-24-spider-man-panel-controversy/ [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

Anonymous. 2024. “Marvel and DC Make It So Hard for Me to Want to Buy Single Issues […]”. r/comicbooks on Reddit, n.d. https://www.reddit.com/r/comicbooks/comments/1bpbqep/marvel_and_dc_make_it_so_hard_for_me_to_want_to/ [Last Accessed 25 February 2025].

Anonymous. 2025. “Gwen Stacy is Back and She's Here to Slay in a New Comic Book Series.” Marvel.com, 18 February. https://www.marvel.com/articles/comics/gwen-stacy-is-back-gwenpool-variant-covers [Last Accessed 22 February 2025].

Aroesti, Rachel. 2025. “The Leopard Review – This Sultry Italian Drama Will Leave You Swooning”. The Guardian, 5 March, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2025/mar/05/the-leopard-review-netflix [Last Accessed 10 March 2025].

Avila, Mike. 2019. “Variant Covers Are Killing Comics... Again.” SyFy, 19 November. https://www.syfy.com/syfy-wire/variant-covers-are-killing-comics-again [Last Accessed 25 March 2025].

Ayres, Jackson. 2021. Alan Moore: A Critical Guide. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Banks, Annie. 2026. “DC’s Jim Lee Admits Manga Has Beaten Western Comics.” CBR, 26 January. https://www.cbr.com/dc-jim-lee-manga-beats-western-comics/ [Last Accessed 30 January 2026].

Barnett, David. 2019. “Why Are Comics Shops Closing as Superheroes Make a Mint?” The Guardian, 26 April. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/apr/26/why-are-comics-shops-closing-superheroes-avengers-endgame [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

Behbakht, Andy. 2023. “Ben Reilly Becomes Most Controversial Element of Across The Spider-Verse.” Screen Rant, 5 June. https://screenrant.com/across-the-spider-verse-ben-reilly-controversy/ [Last Accessed 25 February 2025].

Bowens, Janae. 2025. “Fact Check Team: Divorce Rates Hit Record Low in the US as Marriage Trends Shift.” NBC Montana, 17 January, https://nbcmontana.com/news/nation-world/divorce-rates-hit-record-low-in-the-us-as-marriage-trends-shift-census-data-generation-x-millenials-relationships [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Blumberg, Arnold T. 2003. “The Night Gewn Stacy Died: The End of Innocence and the Birth of the Bronze Age.” Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture 3(4), http://reconstruction.eserver.org/034/blumberg.htm [inaccessible as of February 2025].

Brambilla, Alberto. 2022. “Alex Bertani sta cambiando Topolino.” Fumettologica, 21 Febbraio 2022. https://fumettologica.it/2022/02/topolino-alex-bertani/ [Last Accessed 23 June 2025]

Brevoort, Tom. 2024. “#124: I Buy Crap.” Man with a Hat, 11 August. https://tombrevoort.substack.com/p/124-i-buy-crap [Last Accessed 4 July 2025].

Brevoort, Tom. 2025a. “#150: The Deep and Lovely Dark. We’d Never See the Stars Without It.” Man with a Hat, 9 February. https://tombrevoort.substack.com/p/150-the-deep-and-lovely-dark [Last Accessed 25 February 2025].

Brevoort, Tom. 2025b. “#156: Make New Mistakes.” Man with a Hat, 23 March. https://tombrevoort.substack.com/p/156-make-new-mistakes [Last Accessed 25 March 2025].

Brevoort, Tom. 2025c. “#157: Right at the End, Embarks a New Story.” Man with a Hat, 30 March 2025. https://tombrevoort.substack.com/p/157-right-at-the-end-embarks-a-new [Last Accessed 23 June 2025].

Bryman, Alan. 2005. The Disneyization of Society. London and Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Chatfield, Tom. 2018. Critical Thinking. Los Angeles and London: SAGE.

CBR Staff. 2008. “The ‘One More Day’ Interview with Joe Quesada – The Fans.” Comic Book Resources, 28 January 2025. https://www.cbr.com/the-one-more-day-interview-with-joe-quesada-the-fans/ [Last Accessed 22 February 2025].

Coslett, Rhiannon Lucy. 2023. “The 2000s Lad Culture that Russell Brand Epitomised Wasn’t Funny Then. It Looks Even More Hideous with Hindsight.” The Guardian, 21 September. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/sep/21/2000s-lad-culture-russell-brand-hindsight-women-misogyny [Last Accessed 31 January 2026].

Crowell, Judith A., Dominique Treboux, and Susan Brockmeyer. 2009. “Parental Divorce and Adult Children’s Attachment Representations and Marital Status”. Attachment & Human Development 11(1): 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730802500867

Curtis, Neal. 2019. “Superheroes and the Mythic Imagination: Order, Agency and Politics.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 12(5): 360-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2019.1690015

DeFalco, Tom (ed.). 2004. Comics Creators on Spider-Man. London: Titan Books.

Del Core, Mattia. 2023. Ventenni Paperoni. Ma leggi ancora Topolino? Eboli (SA): NPE.

De Poli, Valentina. 2022. Un’educazione paperopolese. Dizionario sentimentale della nostra infanzia. Milano: il Saggiatore.

Di Nallo, Alessandro, and Daniel Oesch. 2023. “The Intergenerational Transmission of Family Dissolution: How It Varies by Social Class Origin and Birth Cohort.” European Journal of Population 39(1): 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-023-09654-7

Dubourg, Edgar, and Nicolas Baumard. 2022. “Why Imaginary Worlds? The Psychological Foundations and Cultural Evolution of Fictions with Imaginary Worlds.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 45: e276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X21000923

Fiamma, Andrea. 2024a. “Il fumetto di Paperino che diventa Wolverine non funziona.” Fumettologica, 20 August. https://fumettologica.it/2024/08/paperino-wolverine-fumetto-recensione/ [Last Accessed 11 February 2026].

Fiamma, Andrea. 2024b. “Paperino-Thor è meno peggio di Paperino-Wolverine.” Fumettologica, 17 September. https://fumettologica.it/2024/09/paperino-thor-marvel-disney-fumetto-recensione/ [Last Accessed 11 February 2026].

Fiamma, Andrea. 2026. “Com’è stato il 2025 di ‘Topolino’ e come sarà il 2026, raccontato dal suo direttore.” Fumettologica, 9 February. https://fumettologica.it/2026/02/topolino-2025-2026-bilancio-novita/ [Last Accessed 11 February 2026].

Fidecaro, Fabrizio. 2025. Review of Topolino #3629. Papersera, 16 giugno. https://www.papersera.net/wp/2025/06/16/topolino-3629/

Filik, Ruth and Hartmut Leuthold. 2013. “The Role of Character-based Knowledge in Online Narrative Comprehension: Evidence from Eye movements and ERPs.” Brain Research 1506: 94-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2013.02.017

Fingeroth, Danny. 2019. A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee. London and New York: Simon & Schuster.

fjmac. 2023. “Is the Spider-Man Editorial Approach Out of Touch Instead of Just Spiteful?” CBR Community, 6 October. https://community.cbr.com/threads/is-the-spider-man-editorial-approach-out-of-touch-instead-of-just-spiteful.168771/ [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

Fritz, Ben. 2025. “Disney Wanted More From Marvel. Now It Wants Less.” The Wall Street Journal, 2 May. https://www.wsj.com/business/media/marvel-avengers-mcu-robert-downey-jr-dr-doom-311f9ffc#comments_sector [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Gagliano, Gina. 2025. “What Will Potential Tariffs Mean for Comics Publishers in 2025? ‘We’ll Likely Have Less Customers’.” The Comics Journal, 13 January. https://www.tcj.com/what-will-potential-tariffs-mean-for-comics-publishers-in-2025-well-likely-have-less-customers/ [Last accessed 24 February 2025].

Ginocchio, Mark. 2012. “Reading Experience: The Sins Past of J. Michael Straczynski.” Chasing Amazing, 8 February. https://www.chasingamazingblog.com/2012/02/08/reading-experience-the-sins-past-of-j-michael-straczynski/ [Last Accessed 18 March 2025].

Ginocchio, Mark. 2015. “Volume 2 Review: The End of Mackie/Byrne.” Amazing Spider-Talk, n.d. https://amazingspidertalk.com/2015/11/volume-2-review-the-end-of-mackiebyrne/ [Last Accessed 18 March 2025].

Ginocchio, Mark. 2017. 100 Things Spider-Man Fans Should know & Do Before They Die. Chicago: Triumph.

Goletz, Andrew. n. d. “The Ben Reilly Tribute Presents The Life of Reilly.” The Ben Reilly Tribute. https://benreillytribute.x10host.com/LifeofReilly1.html [Last Accessed 24 February 2025]

Gumbel, Andrew. 2025. “‘Not the Charmed Industry It Once Was’: Can Hollywood Find Its Comeback Story?” The Guardian, 26 December. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/dec/26/hollywood-production-film-tv-industry-struggles [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Hart, David. 2021. “Let’s Talk About the Psychology of One More Day.” You Don’t Read Comics, 22 September. https://www.youdontreadcomics.com/articles/2021/9/22/lets-talk-about-the-psychology-of-one-more-day [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Hionis, Jerry, and YoungHa Ki. 2019. “The Economics of the Modern American Comic Book Market.” Journal of Cultural Economics 43 (4): 545-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48698121

Howe, Sean. 2012. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York: HarperCollins.

Isaak, Joshua. 2021. “The Reason Marvel Will Never Undo Spider-Man: One More Day is Tragic.” Screen Rant, 5 October. https://screenrant.com/spider-man-one-more-day-aunt-may-retcon/ [Last Accessed 18 March 2025].

James, M. 2017. “He Believed in ‘Power Rangers’ When Nobody Else Did, and It Turned Him Into a Billionaire.” Los Angeles Times. 19 March. https://www.latimes.com/business/hollywood/la-fi-ct-haim-saban-power-rangers-20170319-story.html [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Johnston, Rich. 2021. “Jonathan Hickman's Departure From X-Men, Explained.” Bleeding Cool, 4 October. https://bleedingcool.com/comics/jonathan-hickman-departure-from-x-men-explained/ [Last Accessed 21 March 2025].

Johnston, Rich. 2025a. “As Court Denies Dynamite Over Diamond, Comic Creators Rally Round.” Bleeding Cool, 3 July. https://bleedingcool.com/comics/as-court-denies-dynamite-over-diamond-comic-creators-rally-round/ [Last Accessed 4 July 2025]

Johnston, Rich. 2025b. “Blindbagonomics And Comics 101 – More Than Just Another Labubu.” Bleeding Cool, 20 September 2025. https://bleedingcool.com/comics/blindbagonomics-and-comics-101-more-than-just-another-labubu/ [Last Accessed 31 January 2026].

Kain, Erik. 2023. “The Madness of The Multiverse: How Infinite Universes Are Killing the Superhero Genre.” Forbes, 14 November. https://www.forbes.com/sites/erikkain/2023/11/14/we-truly-are-living-in-a-multiverse-of-madness-and-it-needs-to-stop/ [Last Accessed 25 February 2025].

Keegan, Rebecca, Alex Weprin, Lacey Rose, Lesley Goldberg, Pamela McClintock, Winston Cho, Rick Porter. 2023. “Now What? The Five Crises Confronting a Post-Strike Hollywood.” The Hollywood Reporter, 11 October. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lists/writers-actors-strikes-end-hollywood-crises/ [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Kemner, Louis and Angelo Delos Trinos. 2024. “Why Japanese Manga Is Outselling American Comic Books in the West.” Comic Book Resources, updated 22 June. https://www.cbr.com/japanese-manga-vs-american-comics-why-more-popular/ [Last Accessed 25 February 2025].

Kennedy, Sheela and Steven Ruggles. 2014. “Breaking Up Is Hard to Count: The Rise of Divorce in the United States, 1980-2010.” Demography 51 (2): 587-598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0270-9

Kukkonen, Karin. 2010. “Navigating Infinite Earths: Readers, Mental Models, and the Multiverse of Superhero Comics.” Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies 2: 39-58. https://doi.org/10.1353/stw.0.0009

Lennen, Alex. 2023. “The Day That Spider-Man Died.” @alexlennen on YouTube, n.d. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IF-iOrJm9iU [Last Accessed 18 March 2025].

Lennen Alex. 2024. “The Spider-Man Who Deserved Better.” @alexlennen on YouTube, n.d. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQg1S9WRLhY [Last Accessed 24 February 2025].

Lippi, Federica. 2016. “La serialità in Giappone.” In Tosti, Andrea. Graphic Novel. Storia e teoria del romanzo a fumetti e del rapporto fra parola e immagine, 777-782. Latina: Tunuè.

Lunghi, Alberto E. 2025. Review of Topolino #3609. Papersera, 26 gennaio. https://www.papersera.net/wp/2025/01/26/topolino-3609/

Lupoi, Marco M. 1991. “Introduzione”. In Speciale Uomo Ragno 2: Il matrimonio. Star Comics, July/August.

Lupoi, Marco M. 1995. “Note e Contronote.” L’Uomo Ragno #176. Marvel Italia, 30 settembre.

MacDonald, Heidi. 2023. “What Ever Happened to the Sales Charts?” Comics Beat, 10 January. https://www.comicsbeat.com/what-ever-happened-to-the-sales-charts/ [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

MacDonald, Heidi. 2025a. “Report: Comics Sales in 2024.” Comics Beat, 6 January. https://www.comicsbeat.com/report-comics-sales-in-2024/ [Last Accessed 23 February 2025]

MacDonald, Heidi. 2025b. “Will the Diamond Bankruptcy Change the Comics Business Forever?” Publishers Weekly, 12 February. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/article/97080-will-the-diamond-bankruptcy-change-the-comics-business-forever.html [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

MacDonald, Heidi. 2025c. “DC Comics Sales: Was DC the Top Comics Publisher in 2025?” Comics Beat, 29 December. https://www.comicsbeat.com/dc-comics-sales-was-dc-the-top-comics-publisher-in-2025/ [Las Accessed 31 January 2026].

Maeda, Kaori. 2026. Jim Lee Interview – “DC Comics CCO: The Success of Japanese Anime Gives Us a Goal.” Nikkei XTrend, 26 January, https://xtrend.nikkei.com/atcl/contents/watch/00013/02780/ [Last Accessed 31 January 2026].

Mazur, Dan and Alexander Danner. 2014. Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson.

McMillan, Graeme, Sharareh Drury, and Aaron Couch. 2020. “Comic Book Industry Reckons With Abuse Claims: ‘I Don’t Want This to Happen to Anyone Else’.” The Hollywood Reporter, 31 July. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/comic-book-industry-reckons-abuse-claims-i-dont-want-happen-anyone-1305217/ [Last Accessed 23 February 2023].

Medina, Cynthia. 2019. “Why Are Manga Outselling Superhero Comics?” Rutgers University, 5 December. https://www.rutgers.edu/news/why-are-manga-outselling-superhero-comics [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

Meenan, Devin. 2024. “Can The X-Men Go Back To The Status Quo After Krakoa?” IGN, 28 June. https://www.ign.com/articles/x-men-relaunch-status-quo-krakoa-from-the-ashes [Last Accessed 25 February 2025].

Mendoza, Xavier. 2024. “The Amazing Spider-Man Can’t be Redeemed.” Godzilla Mendoza YouTube channel, n.d. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PlVfGz_tmg0 [Last Accessed 18 March 2025].

Miracle, Veronica and Gregg Canes. 2025. “What’s Happening to Hollywood? The Mass Exodus of a Shrinking Industry.” CNN Businesss, 22 May. https://www.cnn.com/2025/05/22/business/hollywood-economy [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

@mnstash. 2025. “Ben Reilly Deserved BETTER.” MNStash Youtube channel, September 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RImrOWjk5MA [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Moore, Alan. 1983. “Stan Lee: Blinded by the Hype. An Affectionate Character Assassination. Part 2,” in The Daredevils #4: 46-48. Marvel UK.

Moore, Alan. 1987. “Twilight of the Superheroes.” Internet Archive, https://archive.org/stream/TwilightOfTheSuperheroes/TwilightOfTheSuperheroes_djvu.txt [Last Accessed 7 March 2025]; also available in Johnston, Rich. 2020. “Let's All Read Alan Moore's Proposal for DC Event Comic, Twilight of The Superheroes.” Bleeding Cool, 18 March, https://bleedingcool.com/comics/lets-all-read-alan-moores-proposal-for-dc-event-comic-twilight-of-the-superheroes/ [Last Accessed 7 March 2025]; proposal officially published in Levitz, Paul. (ed.). 2020. DC Through the ’80s: The End of Eras. DC Comics.

Moore, Alan. 2003. The Mindscape of Alan Moore. Documentary directed by De Vylenz. Shadowsnake Films, 78 mins.

Moore, Alan. 2023. Illuminations. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Morris, Regan. 2024. “Hollywood Industry in Crisis after Strikes, Streaming Wars.” BBC News, 28 September. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cj6er83ene6o [Last Accessed 27 January 2026].

Morrison, Grant. 2012. Supergods: Our World in the Age of the Superhero. London: Vintage.

Myrick, Joe Anthony. 2024. “Amid Rising Prices, Some Comic Publishers Are Crashing Under the Industry's Climate.” Screen Rant, 18 November. https://screenrant.com/comics-expensive-price-economy-indie-publishers/ [Las Accessed 24 February 2025].

Myrick, Joe Anthony. 2025. “There Are Things We Want for Spider-Man, But Gwen Stacy's Return Is Not One of Them.” Screen Rant, 19 February 2025. https://screenrant.com/spider-man-marvel-comics-gwen-revival-reaction-op-ed/ [Last Accessed 23 February 2025].

Nam, Michael. 2024. “The Comic Book Industry Has Nearly Died Before. Some Artists Fear AI Will Kill It.” CNN, 31 December. https://edition.cnn.com/2024/12/31/business/comic-books-ai/index.html [Last Accessed 23 February 205].

Nocera, Guglielmo. 2025. Review of Topolino #3637. Papersera, 11 agosto. https://www.papersera.net/wp/2025/08/11/topolino-3637/

Pavan, Federico. 2024. Review of Topolino #3601. Papersera, 4 dicembre. https://www.papersera.net/wp/2024/12/04/topolino-3601/

Powell, Barry B. 2021. Classical Myth. Ninth Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reaves, Charlie. 2025. “Spider-Man May Be an Icon, But Marvel’s Worst Storyline Is Still Holding the Hero Back.” Screen Rant, 20 March. https://screenrant.com/spider-man-controversial-story-comic-ruined-marvel-op-ed/ [Last Accessed 21 March 2025].